Qilin Ransomware – A Double Extortion Campaign

I. Introduction

Ransomware remains one of the most damaging cyber threats to both public and private sectors in the U.S. In 2025, Qilin, also known as “Agenda”, emerged as one of the most active ransomware operations currently targeting organizations worldwide, including U.S. state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) entities [3].

First observed in 2022, Qilin quickly became prominent after the decline of RansomHub in early 2025, absorbing many of its affiliates. Qilin operates under a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) model, in which a core group of cybercriminals develops, advertises, and leases their tools and infrastructure to other affiliate cybercriminals to conduct attacks. This group also uses a double extortion strategy, meaning that in addition to encrypting data and holding the key for ransom, they steal critical data and threaten to sell or release it as an additional form of leverage against victims [3].

This report provides an overview of Qilin ransomware and offers guidance on protecting against its threat actors. Qilin is a ransomware notorious for targeting critical infrastructure, healthcare, manufacturing, and education sectors by exfiltrating their data, encrypting their systems, and leaking confidential information to demand a ransom.

Read through to understand the current threat landscape, including Tactics, Techniques & Procedures, Indicators of Compromise, as well as defensive and mitigation strategies that can be implemented to reduce ransomware risk from the Qilin group.

II. Threat Landscape / Targets

Qilin’s targets are selected by its ransomware affiliates based on opportunity and span across multiple sectors, with the most frequently impacted being manufacturing, education, government, healthcare, critical services, and financial services. The chosen industries are strategically targeted for their high financial value, giving Qilin affiliates a better chance to extort larger ransom payments. These incidents have been observed worldwide, although activity has mostly been observed in North America and Europe. Targets that have been compromised share common infrastructure weaknesses, such as large, distributed networks, legacy systems, and misconfigured remote access services [6, 19].

Qilin’s major attack was on a UK-based healthcare organization called Synnovis. The following examples highlight major attacks between June 2022 and August 2025:

- June 2022 – Initial Discovery (Undisclosed Organization)

- The first known Qilin ransomware case was detected when attackers gained access to a company’s Virtual Private Network (VPN) and compromised an administrator account. Using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP), they pivoted into the organization’s Microsoft System Center Configuration Manager (SCCM) server, establishing persistence for further attacks. No data exfiltration was observed, but three systems were encrypted [6, 9].

- July 2022 – Initial RaaS Appearance as ‘Agenda’

- The group was first observed promoting their Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) tool, named “Agenda,” which was written in the Go programming language and leased to affiliates [2, 20].

- October 2022 – Public Appearance

- Qilin made its first public appearance on a Dedicated Leak Site (DLS) under the name “Agenda,” confirming affiliate operations within the ransomware marketplace [6, 9].

- December 2022 – Technical Evolution

- Qilin was rewritten in the Rust programming language, improving its encryption speed, detection evasion, and cross-platform compatibility [2, 13]

- April 2023 – Manufacturing Sector

- Undisclosed Organization (APAC): A company in the Asia-Pacific region reported being attacked by the new Qilin variant written in Rust. The attackers used SMB, RDP, and WMI for lateral movement and abused default credentials. Approximately 30 GB of data was exfiltrated to MEGA cloud storage over SSL [6, 9].

- January 2024 – Government Sector Attack

- Australian Court System (Australia): Qilin conducted a double-extortion attack targeting the Australian judicial system, exfiltrating sensitive audiovisual court files to pressure the system into paying [6, 19]

- March 2024 – Additional Attacks

- Qilin was linked to additional attacks across different industries and countries, including International Electro-Mechanical Services (U.S.), Felda Global Ventures Holdings Berhad (Malaysia), Bright Wires (Saudi Arabia), PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (Indonesia), Casa Santiveri (Spain) [8].

- May 2024 – U.S. Enterprise Attack

- Undisclosed Organization (U.S.): Qilin compromised a U.S.-based enterprise using default credentials and RDP for initial access and lateral movement. Data exfiltration was observed through FTP [9].

- June 2024 – Healthcare Sector Attack

- Synnovis (UK): Qilin demanded a $50 million ransom after attacking Synnovis, a pathology services provider supporting the UK National Health Service (NHS). The attack disrupted operations of multiple hospitals, caused thousands of appointment cancellations, and resulted in the theft of over 400 GB of patient data [1, 10].

- April 2025 – Corporate Sector Attack

- SK Inc. (South Korea): Qilin affiliates breached the servers of SK Inc., a major investment firm, exfiltrating over 1 TB of confidential corporate data that was later leaked online [6].

- April 2025 – Critical Infrastructure Attack

- City of Abilene (Texas, U.S.): A Qilin attack encrypted city systems and exfiltrated approximately 477 GB of data, resulting in one month of disruption to public services, including the public transit network [14].

- May 2025 – U.S. Government Attack

- Cobb County Government (Georgia, U.S.): Qilin claimed responsibility for exposing the personal and legal data of local government employees and citizens. Over 150 GB of files, including autopsy photos, driver’s licenses, and Social Security numbers, were stolen [5][6].

- June 2025 – Manufacturing Sector Attack

- Shinko Plastics (Japan): Qilin was confirmed to be responsible for a ransomware attack on the Japanese manufacturer Shinko Plastics, claiming to have stolen 27GB of files from the company [11].

- July 2025 – Activity Peak

- Qilin became the most active ransomware group worldwide, claiming 73 victims on its DLS, and demonstrating an increase in activity after recruiting new affiliates [7].

- August 2025 – Additional Manufacturing Sector Attacks

- Qilin claimed responsibility for two confirmed ransomware attacks to the manufacturing sector in Japan, those being Nissan Creative Box and Osaki Medical [11].

With 84 victims between August and September of 2025, the Qilin Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) operation became one of the most active ransomware groups [18].

III. Tactics and Techniques

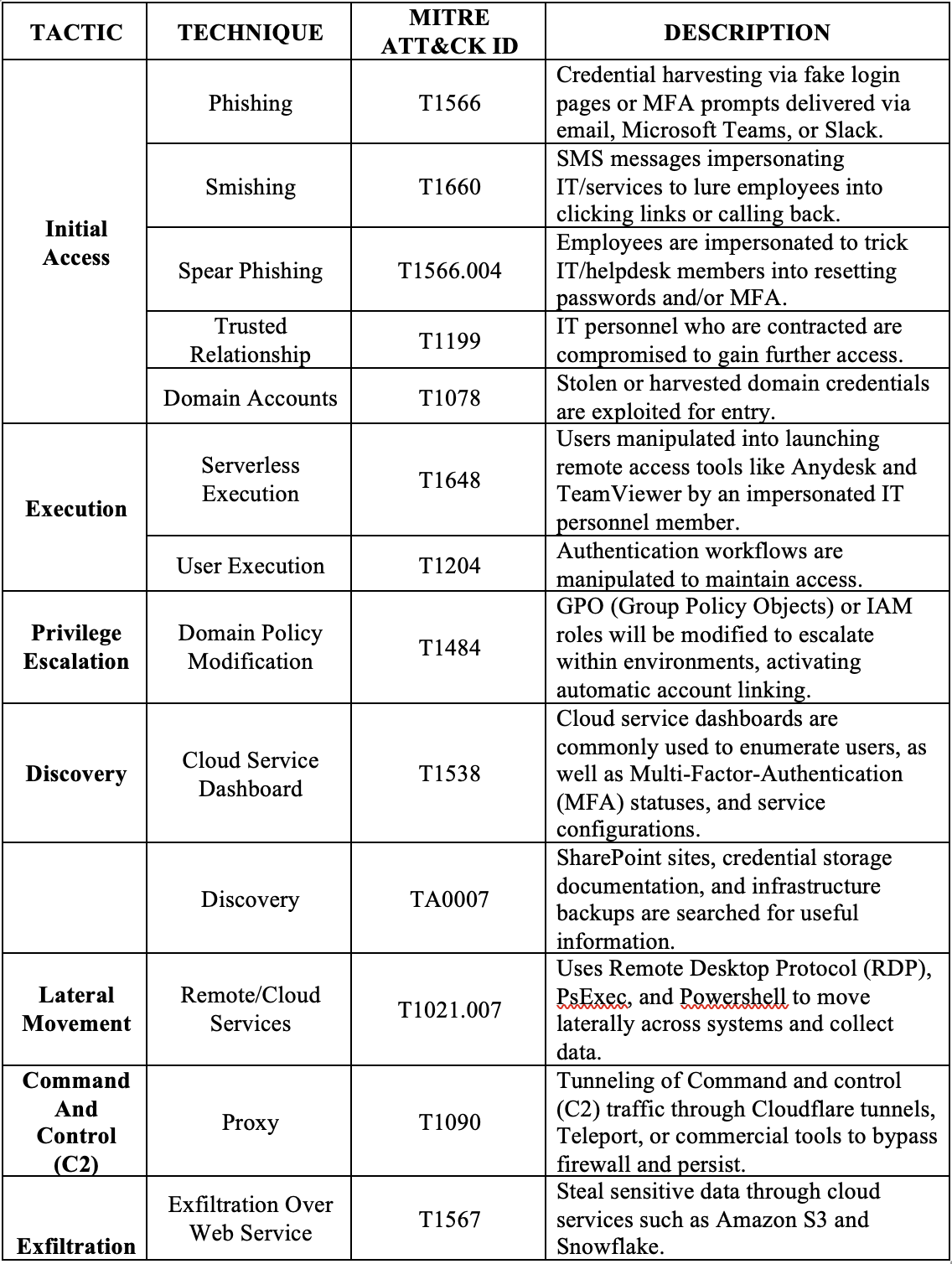

Qilin uses a wide range of Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) to accomplish its goals. They heavily rely on the use of AI-generated content to improve phishing campaigns, create convincing attacks, and avoid detection, be it from harvesting information about their targets or creating believable digital twins. This use of automation and AI-generated content raises the success rate of their attacks [4, 16].

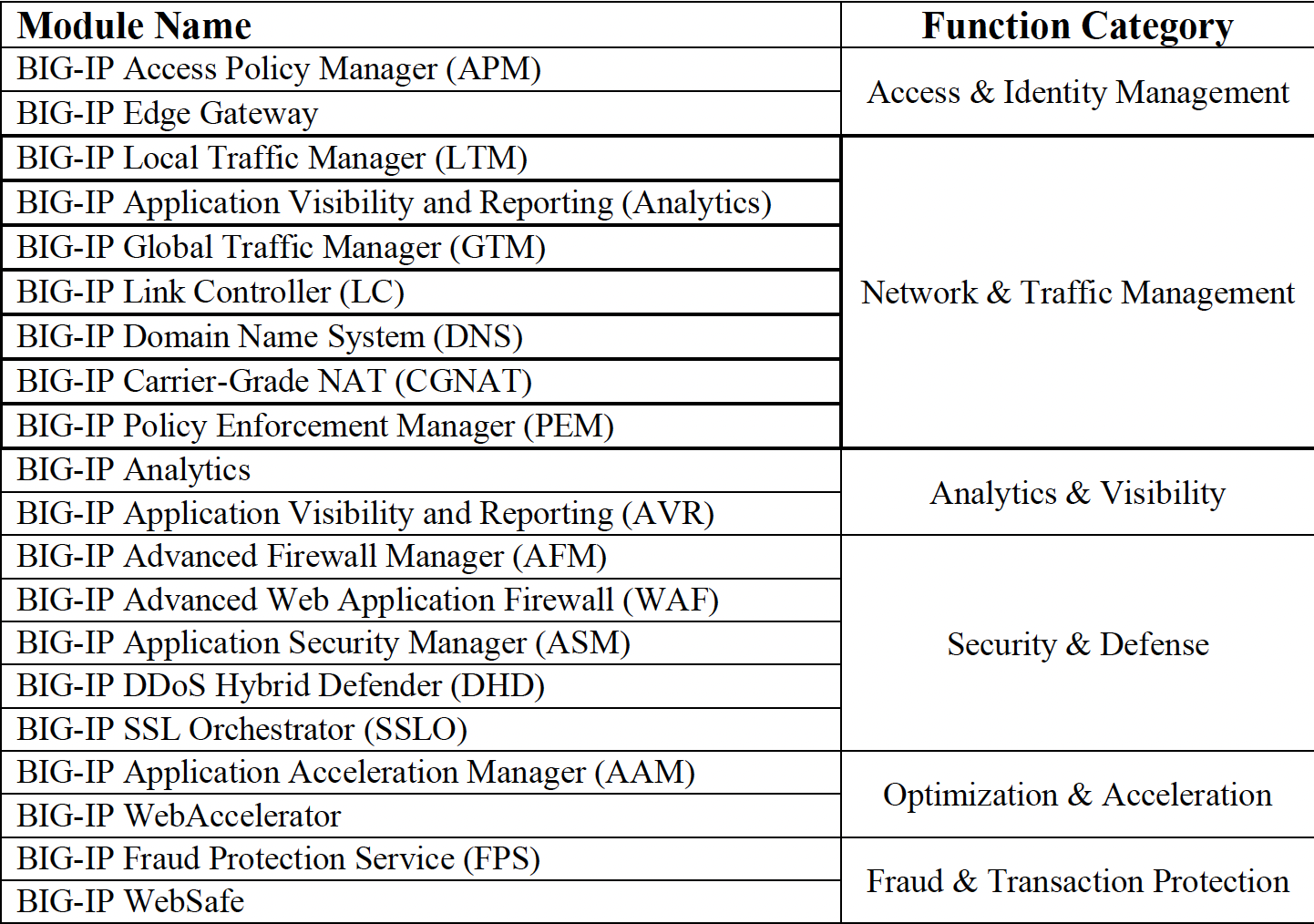

The following table shows their tactics and techniques, along with the corresponding MITRE ATT&CK IDs:

| TACTIC | TECHNIQUE | MITRE ATT&CK ID | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | Exploit Public-Facing Application | T1190 | Qilin threat actors take advantage of the following FortiOS and FortiProxy vulnerabilities [21]:

• CVE-2024-21762 for remote code execution. • CVE-2024-55591 for bypassing authentication. |

| Initial Access | Spearphishing (Attachments and Links) | T1566 |

Qilin threat actors have been observed delivering malware through malicious email attachments and links. [15] |

| Execution | PowerShell | T1059.001 |

Qilin threat actors utilize embedded PowerShell scripts to deploy the Rust variant of Qilin across VMware vCenter and ESXi servers (enterprise virtualization systems) as well as PsExec (a Windows remote-execution tool used for lateral movement) [22]. |

| Execution | Native API | T1106 |

Qilin calls the Native API function “LogonUserW,” supplying valid stolen credentials embedded in its configuration. Since the credentials are valid, Windows creates a normal logon session and returns a usable user token. |

| Persistence | AutoStart via Registry Run Keys | T1547.001 |

After executing, Qilin creates a RunOnce registry entry called “aster” that points to enc.exe, which is a copy of the malware dropped in the public folder. This forces Windows to automatically run the ransomware one more time on the next reboot [23]. |

| Persistence | WinlogonBased AutoStart | T1547.004 |

Qilin ransomware alters Winlogon settings, so Windows automatically runs Qilin executables whenever a user signs in [23]. |

| Persistence | Allowing Network Sharing to Encrypt More Files | T1112 |

Qilin ransomware alters registry settings to make admin-mapped network drives visible on all processes, giving much more access to shared folders, file servers, and network storage that can be used to encrypt data for ransom [23]. |

| Privilege Escalation | Exploitation for Privilege Escalation (BYOVD) | T1068 |

Qilin threat actors may exploit vulnerabilities in legitimate but vulnerable signed drivers (Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver) or other software components to gain higher privileges on compromised hosts, potentially achieving kernel-level access and disabling security controls to facilitate ransomware deployment [23]. |

| Privilege Escalation | Valid Accounts: Domain Accounts | T1078.002 |

Qilin threat actors pivot from a lowaccess Citrix login to a high-privileged leaked/stolen Active Directory account using RDP (a remote-login tool that provides full desktop access), allowing them to push system-wide changes using GPO (Group Policy Objects) to deploy Qilin across the network [23]. |

| Defense Evasion | Delete Artifacts | T1562 / T1070 |

Qilin hides activity by clearing Windows Event Logs, deleting or timestomping files, and self-deleting malware to hinder forensic analysis [16]. |

| Discovery | Cloud Service Dashboard & Backup Discovery | T1538 / T1083 | Qilin threat actors review cloud admin portals to keep track of users, their roles, and whether protections like multifactor authentication are enabled, then search SharePoint, file shares, and backup consoles to locate backup paths, credentials, and snapshots, preparing to disable recovery and prioritize targets [24] |

| Lateral Movement | Remote Services | T1021.002 | Qilin raises MaxMpxCt in Windows to help it spread faster across the network. It embeds PsExec and drops it in %Temp% under a random name to avoid file-based detection [25]. |

| Exfiltration | Exfiltration Over Web Service/Cloud | T1567 | Qilin threat actors zip stolen files into archives using WinRAR. They then open Chrome in Incognito (so the browser would not save history) and upload those ZIP files to easyupload.io, a public file-sharing site, to make it seem like normal HTTPS web traffic [26]. |

| Impact | Data Encrypted for Impact & VSS Deletion | T1486 / T1490 | Qilin threat actors use stolen ScreenConnect consoles to push Qilin to many customers, disable backups to block restores, force Safe Mode with networking so security tools would not start, and delete Volume Shadow Copies to kill rollbacks. They also wipe event logs to hide activity, map more machines to prioritize targets, set a ransom-note wallpaper for leverage, use symbolic links to speed encryption, selfdelete to erase evidence, and encrypt each tenant with a unique 32-character password so one decryptor cannot be reused across victims [26]. |

Table 1. MITRE ATT&CK Techniques Associated with Qilin Ransomware

IV. Adversary Tools and Services

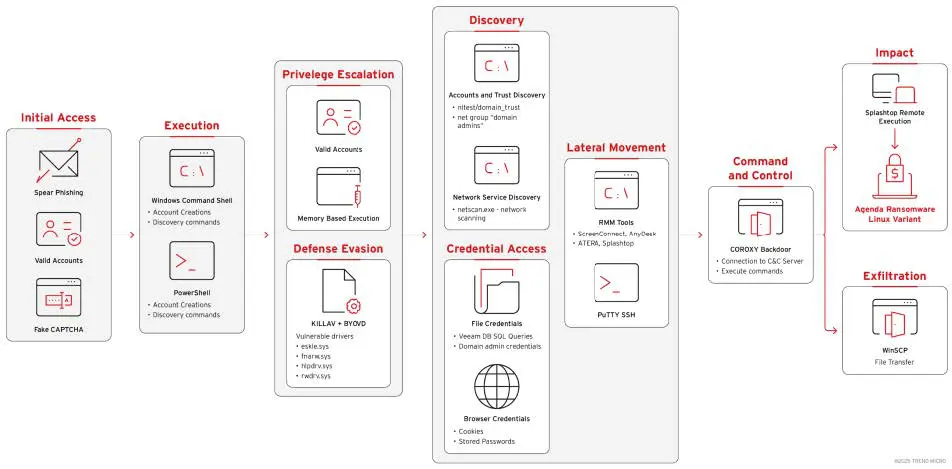

Attackers using Qilin usually gain initial access by using valid accounts, often taken from credential dumps or phishing pages. Once the target is compromised, they move to reconnaissance by using VPN or RDP access to discover endpoints connected to the domain and to map the network, domain trusts, and backup servers for useful targets [18].

In the next stage of the attack chain, attackers harvest credentials with tools such as Mimikatz, search browsers and backup systems for secrets, and abuse those credentials to obtain escalated privileges and to move laterally. Additionally, they deploy legitimate RMM and remote-access software (AnyDesk, ScreenConnect, Splashtop, Atera, etc.) routinely to manage compromised hosts and to load the stage for later activity, and file-transfer utilities (Cyberduck, WinSCP) and common admin applications (mspaint, notepad, iexplore) to scan and harvest for information [18].

To evade detection, Qilin actors use BYOVD (bring-your-own vulnerable driver) exploits, enable Restricted Admin, disable PowerShell-based AMSI/TLS, and disable TLS certificate validation. To tunnel C2 traffic, they use SOCKS proxy DLLs or COROXY implants, sometimes hidden behind RMM infrastructure and legitimate cloud services. For persistent remote access, they were observed using Cobalt Strike and SystemBC [18].

In one recent instance, Qilin actors employed a hybrid approach. They made use of a crossplatform Linux ransomware binary, spreading and executing it on Windows endpoints through remote-management services or safe file transfer. As a result, the group’s presence was amplified on Windows, Linux, and virtualized environments. Altogether, these capabilities make Qilin a significantly dangerous threat [18].

Figure 1. Attack Chain for Qilin Ransomware

V. Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) and Detection Indicators

The table below presents the exact artifacts Qilin used, consisting of: Phishing links and a lookalike ScreenConnect domain, specific installer paths, file hashes of the ransomware and the Veeam exploit tool, Tor/C2 IPs, and the ransom note path. Taken from the GitHub page posted by Sophos Labs called “Ransomware-Qilin-STAC4365.csv” [17], these indicators show how initial access was gained, how tools were deployed, and where encryption and data theft occurred.

| Indicator | Data | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

File Path Name |

C:Users <username> Documents <MSPname> .exe |

Qilin runs code on Windows directly through an executable. The .exe file showed that the ransomware binary was saved and executed as a harmless-looking file in the user’s documents folder, named after the MSP (Managed Service Provider). |

|

SHA256 |

fdf6b0560385a6445bd399eba03c86 |

Hashes representing a different Qilin ransomware executable. They can be traced to the exact malware file, which can help defenders block them. |

|

SHA256 |

0b9b0715a1ffb427a02e61ae8fd11c |

Hashes representing a different Qilin ransomware executable. They can be traced to the exact malware file, which can help defenders block them. |

|

SHA256 |

9da70c521b929725774c3980763a4 |

Hashes representing a different Qilin ransomware executable. They can be traced to the exact malware file, which can help defenders block them |

|

SHA256 |

b52917b0658cd2a9197e6bb62bade |

Hashes representing a different Qilin ransomware executable. They can be traced to the exact malware file, which can help defenders block them. |

|

SHA256 |

ef3e42e5fa24acaee2428ff0118feb2b |

Hashes representing a different Qilin ransomware executable. They can be traced to the exact malware file, which can help defenders block them. |

|

URL |

hxxps[:]//b8dymnk3.r.us-east1.awstrack[.]me/L0/https[:]%2F%2 Fcloud.screenconnect[.]com.ms%2 FsuKcHZYV/1/010001948f5ca748- c4d2fc4f-aa9e-40d4-afe9- bbe0036bc608- 000000/mWU0NBS5qVoIVdXUd4 HdKWrsBSI=410 |

Represents a phishing link hosted on Amazon SES. When clicked, this URL will lead users to a fake ScreenConnect site used for credential and session theft. |

|

URL |

hxxps[:]//cloud.screenconnect[.]co m.ms/suKcHZYV/1/010001948f5ca 748-c4d2fc4f-aa9e-40d4-afe9- bbe0036bc608- 000000/mWU0NBS5qVoIVdXUd4 HdKWrsBSI=410 |

Represents a fake URL used to impersonate ScreenConnect. Qilin threat actors distribute their malware pretending to be ScreenConnect updates. |

|

File Path |

C: Windows SystemTemp ScreenConnect 24.3.7.9067 ru.msi |

A fake ScreenConnect installer used by Qilin attackers to deploy additional payloads to maintain control, disguised as a routine client update. |

|

IP |

186[.]2[.]163[.]10 |

Malicious web host IP with phishing links and installer content |

| IP | 92[.]119[.]159[.]30 | Russian IP that leads to a Russian-hosted server the attacker used to connect to their fake ScreenConnect instance. |

| IP | 109[.]107[.]173[.]60 | Command-and-Control (C2) host used by the attacker as an operational server during the attack. |

| File Path Name |

C: README-RECOVER-<victim ID>. txt |

Text file that holds a ransom note written by the Qilin threat actors. |

| IP | 128[.]127[.]180[.]156 | Tor exit nodes, meaning the attackers routed their traffic through the Tor network to hide their real location. These Tor IPs appeared when they accessed the ScreenConnect server instead of their actual IP addresses. |

| IP | 109[.]70[.]100[.]1 | Tor exit nodes, meaning the attackers routed their traffic through the Tor network to hide their real location. These Tor IPs appeared when they accessed the ScreenConnect server instead of their actual IP addresses. |

| SHA256 | 45c8716c69f56e26c98369e626e0b4 7d7ea5e15d3fb3d97f0d5b6e899729 9d1a |

Hashes that point to the binary Qilin attackers used to exploit Veeam CVE2023-27532. |

| Domain | cloud[.]screenconnect[.]com[.]ms | Fake ScreenConnect domain controlled by Qilin. |

| File Path Name |

C: programdata veeam.exe |

File path that locates where the Veeam exploit tool was saved. |

Table 2. Detection and Monitoring Indicators for Qilin Ransomware

VI. Defensive Strategies & Best Practices

a. Initial Compromise

Threat actors using Qilin RaaS (Ransomware-as-a-Service) packages gain access to enterprise networks through spear-phishing campaigns targeting the C-suite. This can look like emails from unknown users or domains encouraging executives to click on malicious attachments or links designed to replicate legitimate domains. Threat actors also take advantage of legitimate cloud storage services such as OneDrive or Google Drive, making detection more difficult and reinforcing the need for users to recognize suspicious behavior. Staying up to date with security awareness training will equip users with the knowledge to identify typosquatting and report these social engineering attempts, lowering the likelihood of being impacted [3].

b. Reinforce Password Security Policies

Reports from SentinelOne have shown that threat actors were able to gain access to systems with administrator capabilities by exploiting default or weak access credentials. Disabling default credentials and following NIST password security guidance will make it more difficult to gain access to critical systems. NIST 800-53 recommended controls include requiring at least 15- character passwords for privileged accounts, at least 8-character passwords for standard accounts, and comparing passwords against compromised credential databases [15].

c. Diversifying Authentication Methods

Implementing MFA (Multi-Factor Authentication) as well as encouraging passwordless authentication methods like biometrics, hardware tokens, and one-time passcodes will lower the likelihood of a system being accessed if a password is compromised. This implementation is crucial for remote work, as this is a common vector for the abuse of these services [15].

d. Threat Monitoring Tools

Investing in security infrastructure, including EDR, SIEM, and email security tools, specifically those with anti-ransomware capabilities, will aid security engineers in detecting these attacks by analyzing attachments and links for malicious behavior, using behavioral heuristics, comparing file hashes, and detecting lateral movement. Additional defensive measures include securing open ports and performing regular patch and vulnerability management [4].

e. Bolstering Security Defenses

Bolstering security defenses is critical in defending against this ransomware, as users of this tooling are known to abuse remote access through open RDP ports, SSH, VPNs, as well as remote execution to further infiltrate the network. Qilin ransomware is known to exploit unpatched systems, including open ports and services such as Citrix, virtualization, network, and cloud solutions. Keeping up to date with routine software and vulnerability patches will harden devices and limit potential threat vectors that malicious actors can exploit. In instances where these tools must remain available for employees, implementing adaptive security methods (time, geolocation, IP reputation, etc.) will lessen the likelihood of the network being infiltrated without detection [4].

VII. References

[1] BankInfoSecurity. (2024, June 17). UK Pathology Lab Ransomware: Attackers Demanded $50 Million. https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/uk-pathology-lab-ransomware-attackersdemanded-50-million-a-25559

[2] Barracuda. (2025, July 18). Qilin ransomware is growing, but how long will it last? https://blog.barracuda.com/2025/07/18/qilin-ransomware-growing

[3] Center for Internet Security (CIS). (2025, September 11). Qilin: Top Ransomware Threat to SLTTs in Q2 2025. https://www.cisecurity.org/insights/blog/qilin-top-ransomware-threat-to-slttsin-q2-2025

[4] Check Point Software. (2025, July 8). Qilin Ransomware (Agenda): A Deep Dive. https://www.checkpoint.com/cyber-hub/threat-prevention/ransomware/qilin-ransomware/

[5] Cobb County Government. (2025, May 23). Notice of the Cobb County Board of Commissioners Cyber Security Event. https://www.cobbcounty.gov/communications/news/notice-cobb-county-board-commissionerscyber-security-event

[6] CybelAngel. (2025, July 16). Inside Qilin: The Double Extortion Ransomware Threat. https://cybelangel.com/blog/qilin-ransomware-tactics-attack/

[7] Cyble. (2025, August 12). Ransomware Landscape July 2025: Qilin Stays on Top as New Threats Emerge. https://cyble.com/blog/ransomware-groups-july-2025-attacks/

[8] Cyberint. (2025, July 10). Qilin Ransomware: Get the 2025 Lowdown. https://cyberint.com/blog/research/qilin-ransomware/

[9] Darktrace. (2024, July 4). A Busy Agenda: Darktrace’s Detection of Qilin Ransomware-as-aService Operator. https://www.darktrace.com/blog/a-busy-agenda-darktraces-detection-of-qilinransomware-as-a-service-operator

[10] HIPAA Journal. (2024, June 22). Ransomware Group Leaks Data from 300 Million Patient Interactions with NHS. https://www.hipaajournal.com/care-disrupted-at-london-hospitals-due-toransomware-attack-on-pathology-vendor/

[11] Industrial Cyber. (2025, October 08). Qilin hackers claim responsibility for Asahi cyberattack, allege theft of 27 GB of data amid ongoing investigation. https://industrialcyber.co/ransomware/qilin-hackers-claim-responsibility-for-asahi-cyberattackallege-theft-of-27-gb-of-data-amid-ongoing-investigation/

[12] National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). (2025, August 20). How Do I Create a Good Password? https://www.nist.gov/cybersecurity/how-do-i-create-good-password

[13] Quorum Cyber. (n.d.). Agenda Ransomware Report. https://www.quorumcyber.com/malware-reports/agenda-ransomware-report/

[14] S-RM. (2025, July 16). Ransomware in Focus: Meet Qilin. https://www.srminform.com/latest-thinking/ransomware-in-focus-meet-qilin

[15] SentinelOne. (2025, September 17). Agenda (Qilin). https://www.sentinelone.com/anthology/agenda-qilin/

[16] Sophos. (2025, April 1). Qilin affiliates spear-phish MSP ScreenConnect admin, targeting customers downstream. https://news.sophos.com/en-us/2025/04/01/sophos-mdr-tracks-ongoingcampaign-by-qilin-affiliates-targeting-screenconnect

[17] SophosLabs. (n.d.). Ransomware-Qilin-STAC4365 Indicators of Compromise (IoCs). GitHub Repository. https://github.com/sophoslabs/IoCs/blob/master/Ransomware-QilinSTAC4365.csv

[18] The Hacker News. (2025, October 27). Qilin Ransomware Combines Linux Payload With BYOVD Exploit in Hybrid Attack. https://thehackernews.com/2025/10/qilin-ransomwarecombines-linux-payload.html

[19] Tripwire. (2024, June 20). Qilin Ransomware: What You Need to Know. https://www.tripwire.com/state-of-security/qilin-ransomware-what-you-need-know

[20] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (2024, June 18). Qilin Threat Profile (TLP: CLEAR). https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/qilin-threat-profile-tlpclear.pdf

[21] HIPAA Journal. (n.d.). Qilin Ransomware Group Exploiting Critical Fortinet Flaws. https://www.hipaajournal.com/qilin-ransomware-group-exploiting-critical-fortinet-flaws/

[22] BushidoToken. (2024, June). Tracking Adversaries: Qilin RaaS. https://blog.bushidotoken.net/2024/06/tracking-adversaries-qilin-raas.html

[23] Trend Micro. (2022). New Golang Ransomware, Agenda, Customizes Attacks. https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/22/h/new-golang-ransomware-agenda-customizesattacks.html

[24] ThreatLocker. (n.d.). Qilin Ransomware’s Newest Tactics: Widespread Encryption by Any Means Necessary. https://www.threatlocker.com/blog/qilin-ransomwares-newest-tacticswidespread-encryption-by-any-means-necessary

[25] Picus Security. (n.d.). Qilin Ransomware. https://www.picussecurity.com/resource/blog/qilin-ransomware

[26] CyberSecurityNews. (2025). Qilin Operators Mimic ScreenConnect Login Page. https://cybersecuritynews.com/qilin-operators-mimic-screenconnect-login-page/

Threat Advisory created by The Cyber Florida Security Operations Center. Contributing Security Analysts: Eduarda Koop, Waratchaya Luangphairin, and Isaiah Johnson